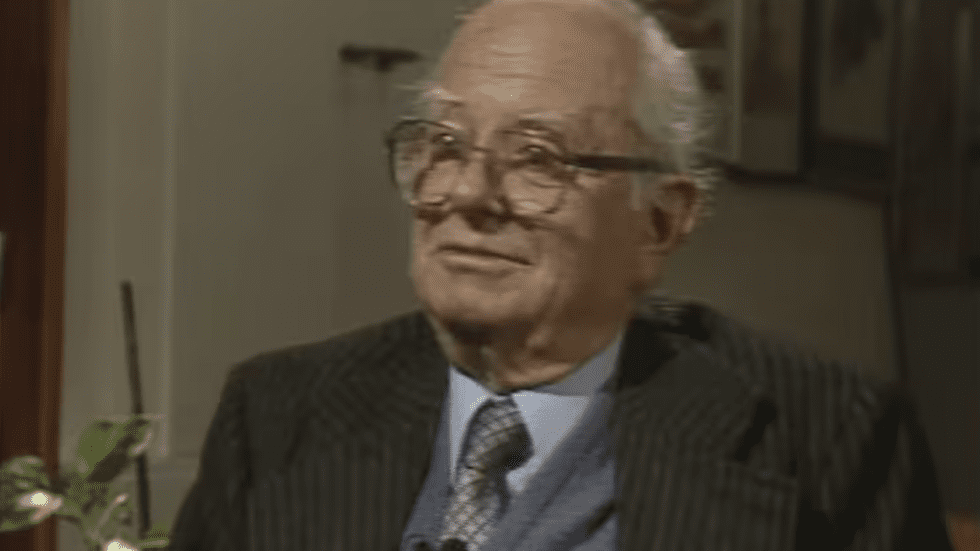

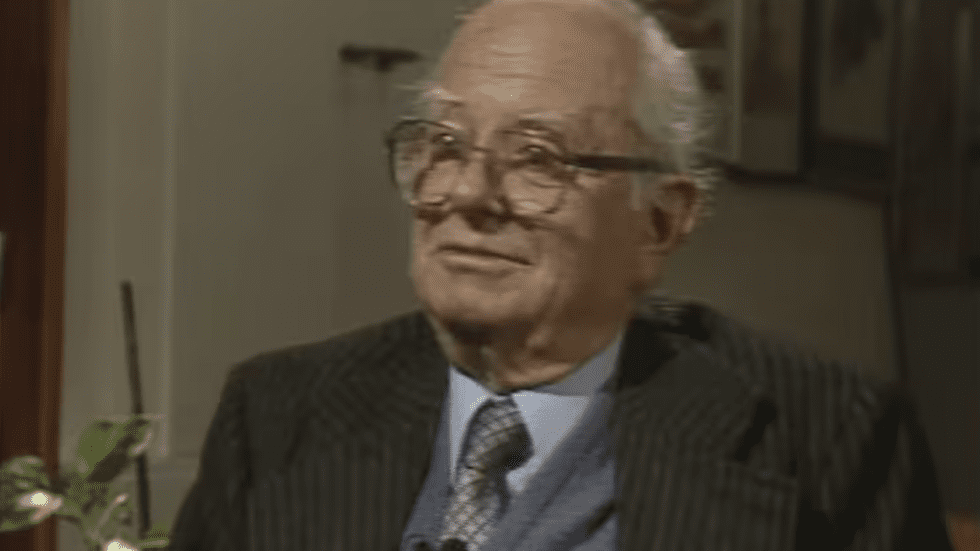

John Pilger talks to Wilfred Burchett

In the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombing of Japan in August 1945, the official lying began. The Allied occupation authorities banned all mention of radiation poisoning and insisted that the victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been killed or injured only by the atomic blast. ‘No radioactivity in Hiroshima ruin’ said the front page of the New York Times, a classic of disinformation and journalistic abdication. There was one exception: the Australian reporter Wilfred Burchett.

‘I write this as a warning to the world,’ reported Burchett in the London Daily Express, having reached Hiroshima after a perilous journey across Japan, the first reporter to dare. Burchett described hospital wards filled with people with no visible injuries, who were dying from what he called ‘an atomic plague’. For telling this truth, his press accreditation was withdrawn, he was pilloried and smeared – and vindicated.

John Pilger first met Wilfred Burchett in Vietnam in the 1970s. ‘I have never known a journalist so at ease in a different culture,’ he said. ‘Wilfred’s empathy with the people of Asia was matched by his remarkable knowledge and understanding of the past and present, and his sense of comradeship. I may owe him my life. He warned me about a planned Khmer Rouge attack on the convoy in which my film crew and I were travelling in Cambodia. When it happened, we were ready.’

Burchett grew up in Gippsland, in rural Victoria, the son of a Methodist minister. He was 19 at the beginning of the Great Depression, which marked him for life. In his autobiography At the Barricades, he wrote that during his wartime reporting behind the lines in Vietnam he would ‘thank his lucky stars’ his legs had found their strength as a young man looking for work.

In The Outsiders, Pilger’s 1983 TV interview series, Burchett describes Hiroshima in 1945 as ‘a city steamrollered’. ‘I was in a state of permanent shock,’ he says. His first dispatch was sent to London via Morse code and was the scoop of the century. For good measure, reported the Brisbane Courier-Mail, ‘armed with a typewriter, seven packets of K rations, a Colt revolver and incredible hope, [Burchett] “liberated” five Allied prison-of war camps’.

Pilger describes Wilfred Burchett as ‘the only Western journalist to consistently report events from the other side in the Korean War and the Cold War, and from China, the Soviet Union and Vietnam’. Bertrand Russell had written, ‘If any one man is responsible for alerting Western opinion to the struggle of the people of Vietnam, it is Wilfred Burchett.’

Although denounced in Australia by the right-wing as a traitor and even denied a passport by the Liberal government, Burchett’s reporting from the communist bloc provided rare insights into what was for most Western journalists a forbidden world — such as North Korea when the war between the North and South, and the United States and China, broke out in 1950. ‘I didn’t have any particular sympathy with North Korea,’ he says, ‘but what I saw was the danger of another world war developing out of that.’

He reported from Moscow, Beijing, the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh and, famously, from Vietnam alongside the National Liberation Front, which the Americans called the Vietcong. He marched and rode on a bicycle down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, survived bombing and witnessed, in villages and underground shelters and hospitals, a people’s resistance to the invasion of a superpower. He recalls Ho Chi Minh as ‘the greatest man I’ve ever met, with all the modesty and simplicity that goes with human greatness’. These were qualities that might well describe Wilfred Burchett, who died shortly after this television interview, aged 72.