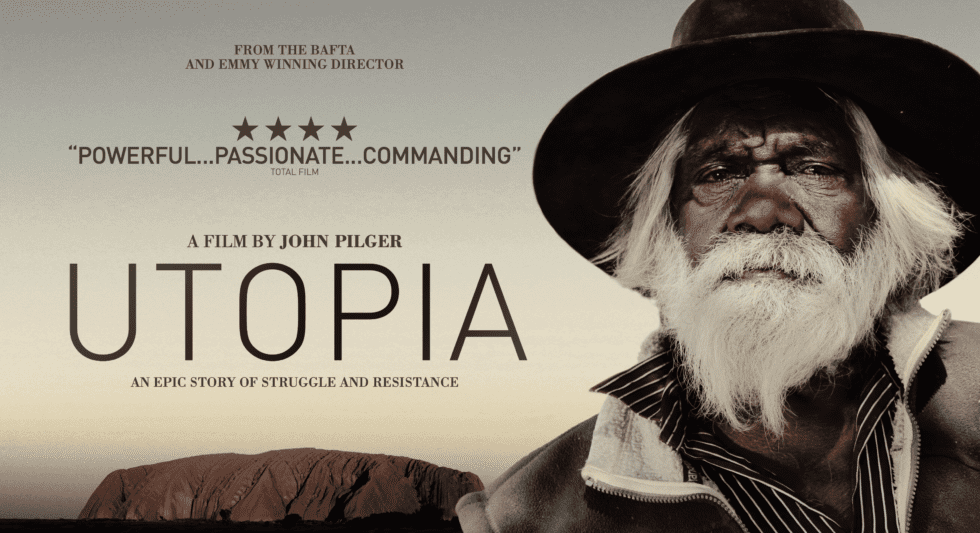

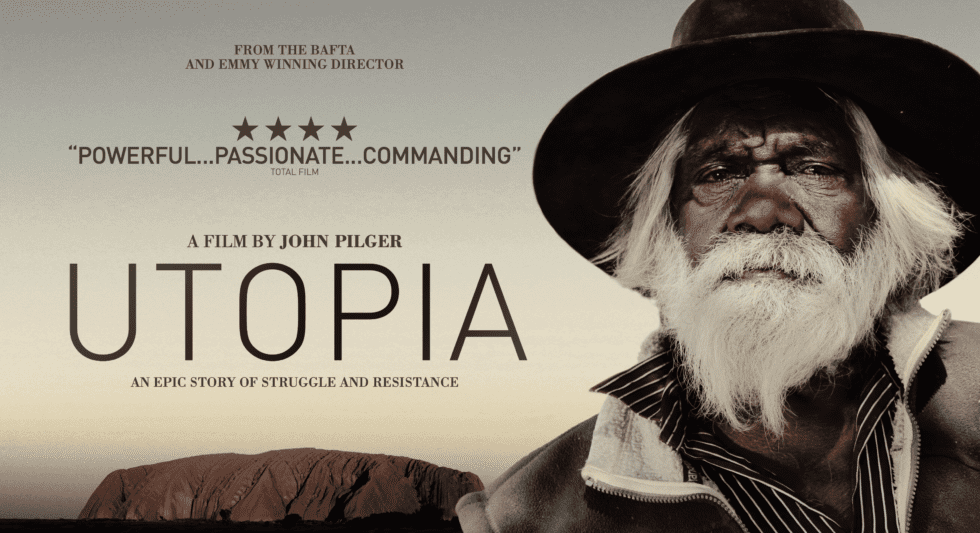

An investigation into Australia’s suppressed colonial past and rapacious present.

Epic in its production, scope and revelations, Utopia represents a long journey through the ‘secret country’ of John Pilger’s homeland. It is his fourth film about Indigenous Australia, the oldest, most enduring human presence on Earth. Released in 2013 and filmed over two years, Utopia breaks what amounts to a recurring national silence about the brutalising of Indigenous people. One of the film’s striking elements is the trust given to Pilger by so many indigenous Australians to ‘voice their voices’.

New footage is juxtaposed with that of his earlier films. The point is made that little has changed for many of those excluded from white Australia’s wealth, regardless of an official apology for ‘wrongs past and present’.

This Australian Tale of Two Cities contrasts the material comfort of the majority with the First Australians who die from Dickensian diseases in their 40s and are imprisoned at a rate six times that of blacks in apartheid South Africa. The state of Western Australia, the richest in the nation, has the highest incarceration rate of juveniles in the world – most of them Indigenous.

Pilger takes a road journey from million-dollar properties in Sydney and Canberra to the ironically named Northern Territory region of Utopia, where communities are without basic services, such as fresh running water. In Darwin, he shows shocking footage of police routinely mistreating a seriously ill Aboriginal man who is left to die in a cell, his cries for help unheeded. A former prisons minister unselfconsciously describes ‘racking and stacking’ Aboriginal prisoners. A shadow Labor Party minister becomes abusive when Pilger asks him why, after 30 years in Parliament, he has not alleviated the poverty of his black constituents. Utopia also reveals, shockingly, a new ‘stolen generation’ of children taken from their mothers.

Pilger returns to the 1981 death of Eddie Murray in custody featured in two of his previous documentaries. Eddie’s parents, Arthur and Leila Murray, became close friends, but Leila is now dead, knowing no justice for her son. Arthur recalls a royal commission’s damning verdict on the police officers who arrested Eddie, yet none was prosecuted. Pilger accompanies Arthur to Eddie’s graveside, where Arthur speaks about his sadness and anger – and justice, which, it seems, is a utopian dream for Australia’s first people.

This sequence ends poignantly with a still photograph of Arthur Murray and John Pilger taken on the riverbank at Wee Waa, where the family grew up. Beneath it are the dates of Arthur’s life – he died shortly after the filming, having promised to ‘keep going long enough, so I can speak up again’.

A centrepiece of the film is an analysis of ‘the intervention’, declared as a ‘national emergency’ in 2007 by Prime Minister John Howard, who sent the army into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. Howard and his Aboriginal Affairs Minister Mal Brough justified this with lurid allegations of Indigenous paedophile gangs.

Communities that refused to hand over the leases of their land were denied basic services such as housing and sanitation, a government job scheme was virtually eliminated and legitimate benefits and pensions were restricted.

Pilger reports that the National Crime Authority, the Northern Territory Police and an investigation by doctors found no evidence to back the hysteria, which happened on the eve of an election. ‘Whether it is Indigenous people or refugees,’ says Pilger, ‘the desperation of voiceless people has been long regarded by Australian politicians as an electorally valuable issue. The real issue, of course, is race, on whose myths and bigoted exploitation Australia was settled.’

Utopia describes how Australia’s multi-billion-dollar mining industry has often ruled politically by ensuring that Aboriginal land claims are scuppered by governments. ‘In 2010,’ Pilger recalls, ‘the mining industry spent A$22 million on a campaign to stop a proposed tax on their super-profits… Labor Prime Minister Julia Gillard reduced the tax to almost nothing. The revenue lost is estimated at A$60 billion, enough to fund land rights and to end Aboriginal poverty.’

In the final sequence, as in his earlier films, Pilger calls for ‘a genuine treaty that shares this rich country, its land, its resources and opportunities [with its first people]. The benefit then will be mutual, for, until we give back their nationhood, we can never claim our own.’

The response to Utopia was unprecedented. The Australian premiere was attended by more than 4,000 people who filled the open space at The Block in Redfern, in the centre of Sydney, and watched the film on a large screen. Indigenous people came from all over Australia, many speaking their own language. As the credits rolled, Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians stood together. This was replicated in towns and remote communities across the country.

‘The atmosphere wherever the film has been shown,’ said associate producer and academic Paddy Gibson, ‘has been electric.’ In Perth, the Noongar elder Robert Eggington wrote, ‘Utopia will live for ever and be like a fire stick in the darkness for all generations to come the more you view it, the more you see it, we are proud of you.’ In the five years since Utopia was released, the long-suppressed issue of a treaty has returned, however tenuously, to a national political agenda.

A subtitled version is also available to watch…