About 100 metres from my home on the edge of the Brisbane CBD is the corner of Boundary and Brereton Streets.

On November 7, 1993, Daniel Yock, an 18-year-old Aboriginal dancer died there. Or at least he was picked up there, by police.

Daniel probably died in the back of a police wagon, like some cattle do on their way to a slaughterhouse. In any event, he was certainly dead by the time he reached the police watchhouse, just a few kilometres from the scene of his arrest.

Daniel Yock’s ‘offence’ was to sit with his friends in nearby Musgrave Park and drink alcohol.

Throughout the afternoon, police circled the block in a wagon. The boys – feeling harassed and intimated – contacted the manager of the local Aboriginal hostel they were staying at. He came down to meet the group, and they decided to head home before dark.

They were tailed by two police officers – Constables Suzette Domrow and Scott Harris – the whole way.

Constable Harris is captured on police radio recordings in the ensuing minutes before Daniel’s arrest.

“There’s about 7 or 8 Aboriginal persons fairly, sort of giving us a few problems and calling us names. They are full of piss, we’d like some persons to come down.”

The recordings show car 591 responded immediately, but was unavailable.

Harris: Yeah, I’ll just get another car. I just thought you might be around ’cause you love that sort of stuff.

Car 591: Yeah, we’d like to but we can’t.

Harris: You would have loved it. No worries. Thank you.”

Alas, no sport today for Car 591.

A few minutes later, Harris called for back-up, and police from around the area swarmed. The group scattered, but Daniel didn’t get far. He was crash tackled to the ground by police.

Multiple witnesses – including white bystanders – reported that after he was brought down, he didn’t move. One of his friends, Glen Gray, could see foam coming from the mouth of a clearly unconscious Daniel Yock. He tried to get police to help. They pushed him back, ignored his pleas.

Yock was dragged unconscious to the paddy wagon, and dumped in the back. His hands were still cuffed behind his back. The police then drove around looking for another youth. One of the boys already in the back with Daniel tried to alert police Daniel’s condition. He was also ignored.

When the wagon finally made it back to the watch house half an hour later, Daniel Yock was likely already dead.

An independent forensic pathologist noted that, with three fresh abrasions to his head, Daniel may have been the victim of a relatively minor assault in the course of his arrest. It had not, however, caused his death. But a pre-existing heart condition meant that Yock’s handling after his arrest – in particular the speed at which arresting officers provided aid in the face of obvious symptoms of severe distress – was crucial.

Needless to say, no police were ever charged over the death of Daniel Yock. A Crime and Corruption Commission inquiry instead recommended “further training” for officers.

Move along, nothing to see here.

That was almost a quarter of a century ago. Today, Daniel Yock would be 42. Most Australians don’t remember his name. Indeed, most Australians would never have even heard of him.

Aboriginal people remember Daniel Yock, and countless others either killed directly by the justice system, or killed by civilians and then let down by the justice system.

This week, Aboriginal Australia has another name to add to a lengthy catalogue of deaths spanning decades – and longer. Deaths which clearly have had little to no impact on a justice system that has always been stacked against them.

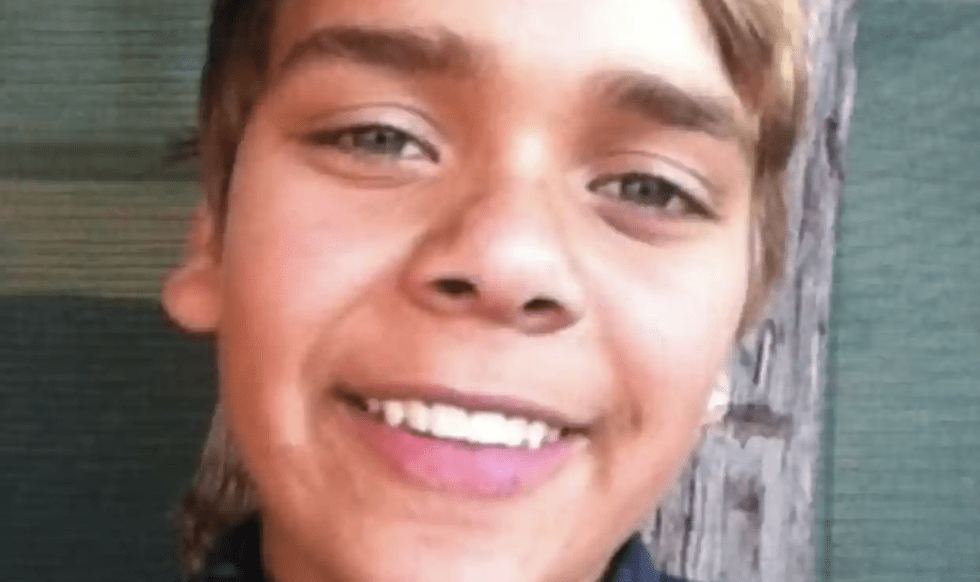

That name is Elijah Doughty (pictured at the top of this article).

In a welcome break from tradition, on this occasion the deceased was not killed at the hands of police. Elijah Doughty was killed by a citizen, a 56-year old Kalgoorlie-Boulder man.

As is now well known, on August 29, 2016, Elijah was riding a stolen motorbike on the outskirts of town. There is no evidence that Elijah stole it, nor that he even knew it was stolen.

The owner had been told the previous day by police that stolen bikes often get dumped in a reserve just out of town. And so the next day, he parked near the reserve, turned his engine off, wound his window down to listen out for bikes, and he waited.

Eventually, Elijah rode past. The man took off in pursuit, driving a large Nissan Navara 4WD ute.

Less than a minute later – around 30 or so seconds – Elijah Doughty was dead. In addition to massive head and internal injuries, his spinal cord was severed at the base of his brain, killing him instantly.

Responding police vehicles and an ambulance drove over the tracks left by the Navara, which made piecing together what happened much more difficult. In the end, investigators had to rely heavily on the man’s version of events – that Elijah was off to the side and in front of his vehicle, but that he suddenly veered in front of the 4WD, and then disappeared under it.

He didn’t have time to stop, he told police.

The man’s defence attorney, told the court: “Ultimately it’s the defence case had the bike not veered in front of (the accused) this wouldn’t have happened.”

That’s certainly one way to put it. You might equally argue that if the man hadn’t taken the law into his own hands, or if local police had done their job in the first place, rather than advise him to go look himself – there might also have been a different outcome.

Regardless, the man’s version of events appears to be the one that police accepted, forming the view that he never intended any harm to come to Elijah Doughty.

That’s why he was charged with manslaughter, not murder. But the man wasn’t even convicted of that. In a Perth court this week, he was instead found guilty of the lesser offence of ‘dangerous driving causing death’, and sentenced to three years jail.

That verdict and sentence, unsurprisingly, has sparked widespread grief and anger from Aboriginal people around the country. But before we turn to why, it’s worth examining briefly what the death, trial and its fallout also sparked: opportunities.

On Saturday morning, Chris Jenkins, a West Australian man who attended a snap vigil in Perth on Friday night, used his Facebook page to describe his interaction with media covering the response to the verdict.

“An important vigil last night for Elijah Doughty and his family…. One thing that really hit home about the treatment of Aboriginal people was when I noticed a cameraman for the ABC. I approached and asked that if the family were willing, would the ABC be interested in doing interviews with them there and then. He replied ‘yeah probably’ but that his brief from higher up had been to pan the crowd and keep an eye out for ‘trouble’, and film that.”

Apparently Channeling Kelly-Anne Conway and her ‘alternative facts’, an ABC executive, Andrew O’Connor, weighed in on Jenkins’ wall a few hours later.

“Hi Chris. I’m the News Editor for ABC News in WA and I want to offer a different perspective and it’s actually the opposite of what you think. Acutely aware of the enduring grief and pain still being felt by Elijah Doherty’s family, friends and the broader community, our reporter and camera operator were trying to remain unobtrusive, not out of fear but out of respect. We were also aware that in the midst of that grief and pain, people may have also felt angry at the outcome of the case.”

A few hundred kilometres west of Perth, here’s a brief snapshot of how the ABC ended up covering the reaction to the verdict in Elijah’s hometown.

“The verdict was greeted with grief and anger outside the courthouse in Kalgoorlie, where people had watched proceedings via a special video link. About 100 people marched down the city’s main street, Hannan Street… The group was tightly flanked by riot police but despite being vocal, there was not the same level of aggression or violence seen in last year’s riot on the same street.”

Presumably, there also wasn’t the same level of “aggression or violence” that saw a 14-year-old boy chased down and killed.

But back to the court process.

There seems little point in debating the outcome. The sentence will likely not be appealed. Justice has been done, say authorities. Move on.

Elijah Doughty’s family will have to make peace with the fact that the man who killed their 14-year-old child will serve, at most, three years behind bars. And they’ll have to make that peace in a climate of collective indifference to their suffering, and the suffering of many, many others.

Unless you’ve lived it, there is no possible way to understand the depth of despair that follows that response. But there is value in understanding why the people of Kalgoorlie rose up last year; why they may again; and why Aboriginal people around the country are once against devastated at the price our society puts on the lives of their children, and their loved ones.

And so, here’s a list of the dead, to help you understand. It’s by no means comprehensive – thousands of Aboriginal people have died without justice over hundreds of years. This list is just intended to provide you a brief snapshot of how our nation kills Aboriginal people, and then responds to their deaths.

Eddie Murray, aged 21

On the afternoon of June 12, 1981 Eddie Murray – a promising young Aboriginal football player – had tried to enter the Imperial Hotel in the north west NSW town of Wee Waa, most likely to use the toilet.

Like the majority of his countryman, Eddie was banned from the Imperial. Indeed, most Aboriginal people were not welcome in the few bars in Wee Waa, a feature of most country towns in Australia.

The doors were locked to keep him out, but Eddie ‘refused to quit’, and so the police were called. He was arrested under the Intoxicated Persons Act 1979, ostensibly for his ‘own protection’.

90 minutes later, Eddie Murray was found hanging from strip of blanket in his cell. A decade later, the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which was sparked in part by Eddie’s death, found two officers lied about the circumstances leading up to the death, but did not pin blame on the police for the actual killing. Eddie’s family never accepted those findings, and a decade and a half later, their disbelief was vindicated.

After the exhumation of Eddie’s remains and an extensive independent investigation, it was found he had a previously undiscovered injury to his chest – his sternum was broken. That had apparently been missed in the autopsy, and thus not canvassed by the Royal Commission.

Medical experts theorized that the most likely cause of the fracture was one or more blows to Eddie’s chest prior to his death, and they questioned how, if he had a broken sternum, he could string himself in his cell.

The mystery was never solved. In the face of compelling new evidence, the NSW Police Minister, Paul Whelan and the Attorney-General, Jeff Shaw – Ministers in Bob Carr’s first cabinet – said they would both seriously consider the new report, and its recommendations. Nothing came of those considerations.

Murray’s parents, Arthur and Leila, campaigned for decades for justice for their son. Leila died in 2003, Arthur died in 2012. Justice eluded them.

In 2014, Eddie’s family refreshed their calls for a new inquiry. The NSW Attorney General, Brad Hazzard indicated he’d like to meet the Murray family to discuss it. Nothing ever came of that either.

Today, Eddie Murray would be 57.

John Pat, aged 16

In September 1983, John Pat, a young Aboriginal boy, was beaten to death by four off-duty police officers outside the Roebourne Hotel.

After the assault, he was arrested and taken back to the local watch house. The officers involved in the fight returned to their drinks at the bar, and later dined at a local restaurant. Police involved in the arrests from the nearby town of Wickham also attended.

Meanwhile, John Pat lay dying in the local watch house from massive head injuries. His jailers did not check on him – instead they falsified an entry in the occurrence book, which was supposed to record regular checks on the welfare of prisoners.

Six witnesses subsequently testified that the off-duty police acted as aggressors in the brawl. Five police were ultimately charged with manslaughter. Each was acquitted unanimously by an all-white jury.

The response from the West Australian Police Union was to demand compensation from the government for their legal expenses (which was paid), before publicly calling for the weakening of the Aboriginal Legal Service, and successfully lobbying against legislative moves to strengthen the power of independent authorities to investigate police.

Today, John Pat would be 50 years old.

Lloyd Boney, aged 28

In August 1987, Lloyd Boney was arrested in the western NSW town of Brewarrina, for a breach of bail conditions from earlier offences. Boney was arrested and dumped in a police cell, heavily intoxicated.

One of the arresting officers, Constable Fernandez, left the station unattended for almost two hours. Lloyd Boney was found hanging in his cell from a football sock.

His body was rushed to Bourke for examination, before his family was even notified he was dead. Police testimony later delivered in court was quaintly described by the Royal Commission as “untrue evidence”.

Like the earlier coronial inquest, the Royal Commission recommended the NSW Police Service consider action be taken against officers over the death. Here’s an excerpt from the Royal Commission about how that went:

“When the coroner recommended that the Commissioner of Police investigate whether there was any breach of Police Instructions arising from the fact that Lloyd had been left unsupervised, a departmental decision was made that Constable Fernandez was guilty of a neglect of duty and that he should be ‘counselled’. All that Constable Fernandez could remember about this counselling was that he was told ‘to take more care with prisoners”.

The fact that the officer was treated “very lightly” was put down to the trauma he suffered as a result of the death, and his “lengthy cross examination” at the coronial inquest.

In the end, no police ever faced charges over the death, but lots of Aboriginal people did. Seventeen of them, in fact, after police were accused of attacking mourners at Boney’s funeral.

The police inspector who led the investigation into the uprising, was the same officer who led the inquiry into Boney’s death, an investigation described as “inadequate” and “blinkered” by the Royal Commission.

Arthur Murray (the father of Eddie Murray) and Albert ‘Sonny’ Bates (Boney’s brother-in-law) were eventually convicted by an all-white jury in Bathurst and sentenced to 18 months jail for affray. That’s half the sentence handed down to Doughty’s killer.

Police at the uprising were given bravery medals.

By way of postscript, two decades later, in 2011, Sonny Bates would be jailed again, this time for sparking a 12-hour siege at a solicitor’s office in Parramatta with a fake bomb threat. No-one was injured. Bates was jailed for almost three years, the same sentence as Doughty’s killer.

Sadly, taunting mourners at the funeral of Lloyd Boney wasn’t the only way police responded to the death. Here’s a video that emerged in 1992 of two police turning up to a fancy dress charity fundraiser in NSW country town.

The video, which was filmed in 1989, also mocked the death of David Gundy, who was shot and killed a few months earlier. Gundy had been sleeping in his bed when police stormed his inner-Sydney home during a bungled (and illegal) raid in search of another man. At the time, the president of the NSW Police Association described the video as just a bit of harmless fun.

Lloyd Boney would be 58 today.

Colleen Walker, aged 16; Evelyn Greenup, aged 4, Clinton ‘Speedy’ Duroux, aged 16

From September 1990, to February 1991, children began disappearing from the Aboriginal mission in Bowraville, on the NSW mid north coast.

In the space of six months, Colleen Walker, aged 16, Evelyn Greenup, aged 4, and Clinton ‘Speedy’ Duroux all went missing.

Police decided Walker had ‘gone walkabout’, and refused to properly investigate. At one stage, police told Walker’s mother, Muriel Craig Walker, to come to the police station – her daughter had been found on a bus heading north. When Muriel arrived, police realised it was the wrong Colleen Walker (they found an elderly nun, not a young Aboriginal woman). Muriel never heard from the Bowraville police again.

When Evelyn Greenup – a baby – disappeared a few months later, police responded by sending in child abuse investigators to probe the Aboriginal community.

Those investigations continued until a few months later, when the body of Clinton Duroux was discovered in nearby bushland, two weeks after he went missing. Police finally realised they had a serial killer on their hands.

In the course of police investigations, it transpired that a set of weights – believed to be one of the murder weapons – was returned to the chief suspect, and that independent witness testimony was never followed up.

A local white man, Jay Hart was eventually charged, but acquitted in two separate trials (Greenup and Duroux).

Police have since admitted and apologised for comprehensively bungling the investigation, and wrongly blaming the community for the deaths.

But still, no-one was behind bars. The victims’ families and the broader Bowraville Aboriginal community kept fighting, for more than two decades. In November 2011, after yet another failed attempt to force the government to act, the NSW Deputy Premier, Andrew Stoner gave the families a commitment he would contact them with details of their fresh appeal. They never heard from him.

Finally, thanks to an extraordinary investigation that spanned more than a decade, led by NSW Police Detective Gary Jubelin, the government was forced to act in the face of ‘compelling new evidence’. Hart was been recharged with the murders, and the trial is awaiting the outcome of an appeal.

No police were ever sanctioned over the failed investigation.

Colleen Walker and Clinton Duroux would be aged 43 today. Evelyn Greenup would be 31.

Mulrunji Doomadgee, aged 36

If the Bowraville Murders sum up the indifference to Aboriginal deaths by the Australian justice system, then death of Mulrunji Doomadgee sums up its deceit.

In 2004, Mulrunji was beaten to death on the floor of the Palm Island police station, off the coast of Townsville in northern Queensland.

Mulrunji’s crime was offensive language – he sung ‘Who let the dogs out’ as he walked past a police officer arresting another Aboriginal man.

About 45 minutes after he was thrown into the back of the police van, Mulrunji had bled to death on the floor of the local watch house. In the course of the police assault on Mulrunji, he suffered multiple injuries, including having his liver “cleaved in two”. His injuries were consistent with a plane crash, and even if he had been transported immediately to hospital, he could never have survived.

The man who killed Mulrunji was Senior Sergeant Chris Hurley, the highest ranking officer on the island and at six foot six inches tall and well over 100 kilos, twice the size of Mulrunji.

Within hours of the killing, Hurley, was drinking beer with the police sent to investigate him, at least one of whom was a close friend.

A pathologist’s report – which was completed without police revealing that an officer stood accused of assault – found that Mulrunji died after tripping up a single step entering the police station, and falling onto a flat floor.

The Aboriginal community responded by burning the police station, the courthouse and Hurley’s barracks to the ground.

Hurley was placed on fully-paid leave, then promoted to acting Inspector, but not before fraudulently collecting an ex-gratia payment from the Beattie Labor Government of more than $102,995 for property he claimed he lost in the fire, which had already been paid out by insurers to the value of $34,980.

Aboriginal people weren’t so lucky. The man who shared a cell with Mulrunji, and comforted him as he screamed in agony and died, took his own life a few years later. Mulrunji’s son killed himself a week before his father’s inquest was set to begin.

More than a dozen Aboriginal people were jailed over the uprising, while – like the uprising in Brewarrina over the death of Lloyd Boney – police on Palm Island received bravery medals.

Hurley was acquitted in 2007 for the manslaughter of Mulrunji. He was finally suspended from the police force more than a decade later, after grabbing the wrist of a female Police officer while off-duty.

Hurley remains suspended from the Police Service, but is expected to be allowed to retire as medically unfit some time this year.

Lex Wotton, the man who led the uprising on Palm Island – the injuries from which totalled a bruise to the hip of a police officer – was sentenced to seven years in prison. That’s more than twice the sentence Elijah Doughty’s killer received.

Mulrunji would be aged 49 today.

Mr Ward, aged 47

On Australia Day, 2008 Mr Ward, a respected Aboriginal man, was picked up by Laverton Police in the West Australian desert for drink driving.

He was refused bail – illegally – and then transported hundreds of kilometres south to Kalgoorlie.

Mr Ward didn’t survive the journey. He was cooked to death in the back of a privately contracted prison van, the air-conditioning of which was not working.

A coronial inquest revealed the heat was so intense in the back of the van that Mr Ward suffered fourth degree burns to his body. After collapsing to the floor, a hole was burnt through his skin, exposing his organs.

No-one has ever been held criminally liable for Mr Ward’s death, despite several warnings delivered to the WA Department of Justice that the fleet of prison transport vans were dangerous.

Mr Ward would be aged 56 today.

Kwementyaye Ryder, aged 33

On July 25, 2009 Kwementyaye Ryder was kicked to death by five white youths in Alice Springs. His ‘crime’ had been to throw a bottle at their car, after they’d driven at him and a group of people sleeping in the dry bed of the Todd River.

Amid a 12-hour binge drinking session, the youths had earlier driven home to retrieve a replica firearm, which they then aimed and fired at terrified Aboriginal campers.

The boys – Scott John Doody, Timothy Hird, Anton Kloeden, Joshua Benjamin Spears and Glen Anthony Swain – were described by the judge, Brian Martin as otherwise upstanding citizens.

A few days after the murder – and before the killers had even been identified – the local council passed laws that criminalised begging, and allowed rangers to throw away blankets which were routinely stored in bushes in the river bed by homeless people, to help them survive the freezing Alice Springs winter.

One local man responded by selling “White power Alice Springs” t-shirts from the back of his car, directly outside the council chambers. I managed to interview him by phone at the time. He told me he’d “done time for flogging the fuck out of some coons” and added, “go and see the fucking coon camps, the coon creeks. they couldn’t invent the fucking wheel.”

Like the killer of Elijah Doughty, the youths escaped with little jail time. They served between 12 months and three and a half years, having been charged with the lowest level of manslaughter.

Kwementyaye Ryder would be aged 41 today.

Kwementyaye Briscoe, aged 27

In January 2012, Kwementyaye Briscoe was picked up by Alice Springs police for being intoxicated.

That’s three full decades after Eddie Murray – whose death helped spark the Royal Commission – was taken into police custody for precisely the same reason. For his protection.

Video footage from the watch house shows how NT police protect vulnerable Aboriginal people. At one point, Mr Briscoe is flung head first into the front counter, and then forced to the floor by police. He’s dragged off to the cells, before police return to mop up his blood from the reception area.

Mr Briscoe is dumped face down in his cell and then left unattended for more than two hours while police surfed the internet, listened to music with headphones, and ignored the pleas of other prisoners for help.

Despite the video evidence, and a coroner’s investigation, no charges were ever recommended let alone laid against police.

Mr Briscoe would be aged 32 today.

Ms Dhu, aged 22

On August 4, 2014, Ms Dhu, a Yamatji woman, died in a South Hedland police cell in Western Australian.

She’d been locked up by police for three days over unpaid fines. In the course of her incarceration, she complained repeatedly of agonising pain.

Police thought she was faking.

Even three separate visits to the local hospital didn’t save Ms Dhu – medical staff on two occasions gave her a cursory examination, and sent back to the watch house with minor pain relief.

Ms Dhu, who had a broken rib, was deemed by all to simply be a black junkie coming down off drugs.

A subsequent coronial investigation acknowledged the failings of police and medical staff, however no charges were recommended, and none have been laid.

The coroner did, however, actively try to prevent the broadcast of CCTV footage of Ms Dhu in custody, despite her family calling for it to be publicly released.

On one occasion, the footage shows police entering her cell, trying to lift her then letting her go and watching her head slam into the concrete floor.

She’s then dragged from the cell along a corridor and dumped into the back of a police van, for her third and final trip to hospital.

Ms Dhu died shortly after of septicaemia and pneumonia.

Ms Dhu would be aged 25 today.

Some of these deaths are at the hands of police. Like the death of Elijah Doughty, some are at the hands of ordinary citizens. But all of them have one thing in common – at varying points along the way, the victims and their families were failed spectacularly by Australia’s justice system.

The list above represents a tiny proportion of the failures, which are ongoing, and perpetrated in broad daylight. For the past few weeks in Alice Springs – one of only a handful of towns that could rival Kalgoorlie for its endemic racism – local residents have been openly calling for the slaughter of Aboriginal people (in particular children) on social media. That’s been going on for years, and attracts the same response from police and authorities. Precious little. People are rarely if ever charged.

Prior to and following the death of Elijah Doughty, precisely the same thing occurred on Kalgoorlie social media pages, with the same limp response from authorities. We don’t just ignore the truth of our past Down Under, we actively ignore the truth of our present as well.

This catalogue of failures by the criminal justice system is well known to Aboriginal people. They live it and confront it every day. There could barely be an Aboriginal family in this country not touched by these tragedies, or let down by those charged to protect them.

It is a fact of life that tragedies happen, that people die, sometimes children. But when it happens in Australia, to those most brutalised and marginalised, our collective response is almost always found wanting. It is either one of silence, or faux sympathy, and never with any real effort to challenge and change a system that routinely delivers the outrages.

This is what non Aboriginal Australians say when children like Elijah Doughty die: ‘There’s no winners here’. ‘This is a tragedy’. ‘That poor man will have to live with this for the rest of his life’.

Yes. Live. Precisely. He will live. He gets to rebuild his life. Elijah Doughty doesn’t. Neither does Elijah Doughty’s family. But the killer won’t need as much time to rebuild his life as you might think. Apart from having his name suppressed, so that he will never have to face any public scrutiny for his actions, it’s been widely reported that he received a three-year jail term.

That’s true, he did. But his sentence was also marked ‘eligible for parole’.

Counting time served since August last year, he may get out of jail as early as February next year, in eight months time. The only way it could get more deliberately outrageous is if authorities chose February 2 – the official date of Groundhog Day – for his release.

Either way, a man who chased down, ran over and killed a 14-year-old Aboriginal boy will, in all likelihood, serve less than two years for his crime.

That’s the price our nation places on the life of an Aboriginal boy. What’s so tragic is that logically, Aboriginal people should probably feel grateful that he’ll served any time at all.

Chris Graham is the publisher and editor of New Matilda, Australia (www.newmatilda.com). He is the former founding managing editor of the National Indigenous Times and Tracker magazine. Chris has won a Walkley Award, a Walkley High Commendation and two Human Rights Awards for his reporting. He was an associate producer on John Pilger’s 2014 film, Utopia.