The shocking state of Cambodia after Pol Pot’s murderous regime.

John Pilger’s shocking 1979 documentary Year Zero: The Silent Death of Cambodia alerted the world to the horrors wrought by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge. The film was originally broadcast on commercial television in Britain and Australia without advertising, which was unprecedented. The British Film Institute lists Year Zero as one of the 10 most important documentaries of the 20th century.

Pilger reveals that as many as two million people out of a population of seven million were killed or starved by Pol Pot’s medievalists. ‘The genocide of Pol Pot,’ he says, ‘was begun by Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger.’ The film is replete with evidence that the US bombing of Cambodia from 1969 to 1973 caused such turmoil that the rise of the Khmer Rouge to power in 1975 was made inevitable.

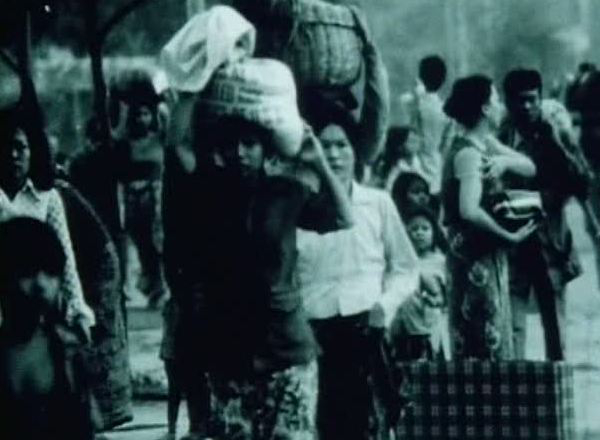

In his introduction, Pilger says to the camera, ‘The new rulers of Cambodia called 1975 Year Zero, the dawn of an age in which there would be no families, no sentiment, no expressions of love or grief, no medicines, no hospitals, no schools, no books, no learning, no holidays, no music, no song, no post, no money; only work and death… For me, coming here has been like stumbling into something I could never imagine and what follows is the first complete film report by Westerners from the ashes of a gentle land.’

With director David Munro, camera operator Gerry Pinches, sound recordist Steve Phillips and photographer Eric Piper, Pilger arrived in Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, ‘as if in the wake of a nuclear war that spared only the buildings’.

‘Nothing had prepared us,’ he said. ‘There was no power, no drinking water, no shops, no services of any kind. At the railway station, trains stood empty at various stages of interrupted departure. Personal belongings and pieces of clothing fluttered on the platforms, as they fluttered on the mass graves beyond.

‘I had no sense of even the remains of a population. The few human shapes I glimpsed seemed incoherent and, on catching sight of me, would flit into a doorway. A child ran into a wardrobe lying on its side which was his or her refuge. In a crumbling Esso filling station, an old woman and three emaciated infants squatted around a pot containing a mixture of roots and leaves, which bubbled over a fire fuelled with paper money. Such grotesque irony: people in need of everything had money to burn.’

At Tuol Sleng extermination centre, where men, women and children were tortured and killed, black-and-white photographs of the victims stare out of the screen. Outside, deserted streets are interrupted by the lone figure of an infant – his parents almost certainly dead or missing – weaving his way down the middle of the road.

Everyone Pilger meets has lost at least six family members. Perhaps the most shocking pictures are those of emaciated children fighting for their lives, most of them dying from starvation or nutrition-related illnesses that are preventable and curable in the West. Gerry Pinches filmed the children through his own tears.

Pilger’s spontaneous, vivid reporting of the power politics that caused such suffering is a model of anger suppressed. He describes how, as a means of punishing the Vietnamese, whose army had liberated Cambodia (having just liberated its own country from the Americans), the United States and its allies declared a blockade on stricken Cambodia.

Unicef’s representative, Jacques Beaumont, says, ‘In one of the very poor barracks with practically nothing, there was already 54 children dying. One of them was sitting in the corner of the room with swollen legs because he was starving. He did not have the strength to look at me or to anybody. He was just waiting to die. Ten days later, four of these children were dead and I will always remember that, saying: “I did not do anything for these children, because we had nothing.”’

The International Red Cross representative, François Bugnion, took Pilger aside and asked him if he could contact ‘someone in the Australian government who can arrange for an aircraft to fly in a truck, food and drugs to save thousands of lives while the politics are being ironed out’. Pilger later describes his failed attempt to get a response from the Australian ambassador in Bangkok.

Near the end of the film, he refers to a starving boy whose screams can be heard rising and falling in agony. ‘Of course,’ he says directly to the camera, ‘if you’re in Geneva or New York or London, you can’t hear the screams of [this] little boy.’

Year Zero’s broadcast in Britain had a phenomenal public response. Forty sacks of post arrived at the ATV studios in Birmingham, with £1 million in the first few days. ‘This is for Cambodia,’ wrote an anonymous Bristol bus driver, enclosing his week’s wage. An elderly woman sent her pension for two months. A single parent sent her savings of £50.

Screened in 50 countries and seen by 150 million viewers, Year Zero was credited with raising more than $45 million in unsolicited aid for Cambodia, which helped rescue normal life: it restored a clean water supply in Phnom Penh, stocked hospitals and schools, supported orphanages and reopened a desperately needed clothing factory, allowing people to discard the black uniforms the Khmer Rouge had forced them to wear.

Year Zero won many awards, including the Broadcasting Press Guild’s Best Documentary and the International Critics Prize at the Monte Carlo International Television Festival. Pilger himself won the 1980 United Nations Media Peace Prize for ‘having done so much to ease the suffering of the Cambodian people’.

Pilger made a total of five documentaries on Cambodia with his close friend David Munro. Their later films reported on the American and British governments’ back-door support for the exiled Khmer Rouge. In 2008, the former SAS soldier Chris Ryan, then a bestselling author, lamented in a newspaper interview that ‘when John Pilger, the foreign correspondent, discovered we were training the Khmer Rouge in the Far East [we] were sent home’. David Munro died in 1999.