2016. John Pilger’s 60th documentary is both a warning and an inspiring story of resistance.

When the United States, the world’s biggest military power, decided that China, the second largest economic power, was a threat to its imperial dominance, two-thirds of US naval forces were transferred to Asia and the Pacific. This was the ‘pivot to Asia’, announced by President Barack Obama in 2011. China, which in the space of a generation had risen from the chaos of Mao Zedong’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ to an economic prosperity that has seen more than 500 million people lifted out of poverty, was suddenly the United States’s new enemy.

The build-up of naval forces would reinforce the US’s already overwhelmingly superior military position in the region. Seldom referred to in the Western media, 400 American bases surround China with ships, missiles and troops, in an arc that extends from Australia north through the Pacific to Japan, Korea and across Eurasia to Afghanistan and India.

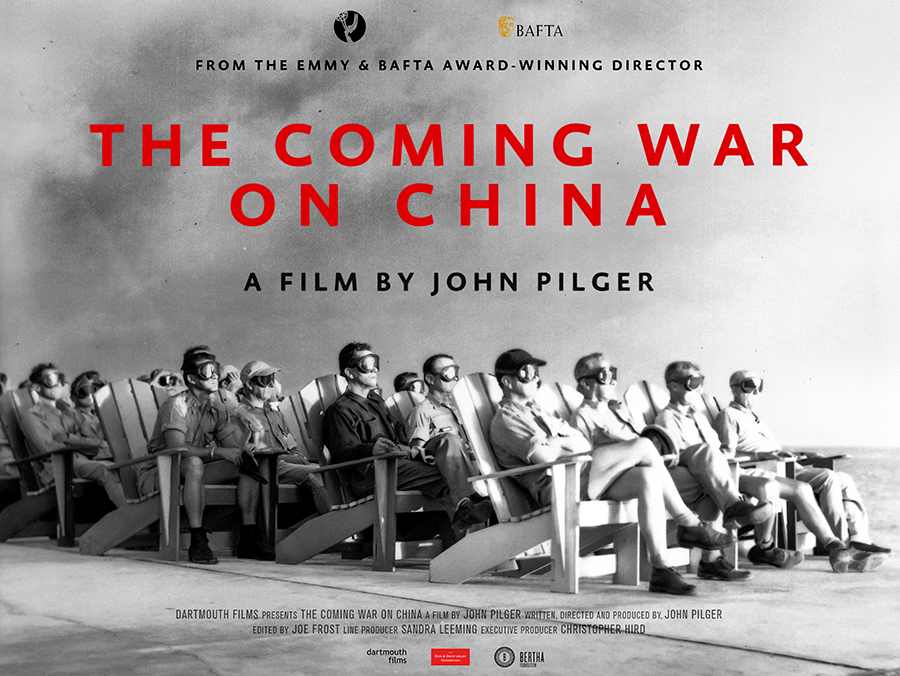

The Coming War on China is John Pilger’s most recent film – his 60th documentary and arguably his most prescient. Completed in the month Donald Trump was elected US President, the film investigates the manufacture of a ‘threat’ and the beckoning of a nuclear confrontation.

The film is marked in chapters. Chapter 1 is set in the remote Marshall Islands, in the Pacific, which the United States took over as a United Nations ‘trust territory’ in 1945 with an obligation to ‘protect the population’s health and wellbeing’. From 1946 to 1958, the US exploded the equivalent of one Hiroshima bomb every day in the islands, contaminating its people and environment.

Filming on irradiated Bikini Atoll, which cannot be safely inhabited today, perhaps ever, Pilger describes the testing in 1954 of the world’s first hydrogen bomb, codenamed Bravo, which vaporised an entire island, leaving a dark chasm a mile wide in Bikini’s beautiful lagoon. The inhabitants had been moved to a nearby atoll, Rongelap, where the ‘unexpected’ fallout endowed them with multiple cancers.

Declassified documents describe a secret programme originally designed to test the effects of radiation on mice and used in the Marshall Islands on human beings. A US Atomic Energy official of the time describes the island of Rongelap as ‘by far the most contaminated place on Earth’.

The human guinea pigs were regularly monitored and underwent scientific examination. Many suffered thyroid cancer, deformities appeared in babies and countless survivors of the original blast died from radiation poisoning. A claims tribunal was set up and quickly ran out of money. The most moving interviews in the film are with islanders, mostly elderly women, who have survived, precariously, in poverty.

Today, the largest of the Marshall Islands, Kwajalein, is home to one of the United States’s most secretive bases, a missile launch pad designed as a ‘stepping stone to Asia and beyond’ and aimed at China.

Chapter 2 describes China’s remarkable rise. Using rare archive film, Pilger describes ‘the century of humiliation’, when the Chinese were depicted as the ‘yellow peril’ in the West and racial stereotypes were a staple of Hollywood. Author James Bradley describes the opium trade and the colonisation by Britain and the other imperial powers. ‘The American industrial revolution was funded by huge pools of money… from illegal drugs in the biggest market in the world, China,’ he says.

The 1949 Communist revolution marked the end of foreign exploitation but also, ironically, the beginning of a China that almost no ‘expert’ in the West had predicted. ‘Today,’ says Pilger, standing against the ultra-modern skyline of Shanghai, ‘China has matched America at its own great game of capitalism – and that is unforgivable.’

Four hundred miles away, on the Japanese island of Okinawa, 32 American military installations form the front line of a coming war with China. Fumiko Shimabukuro, aged 87, is one of the leaders of a non-violent resistance challenging Washington’s ‘pivot to Asia’. They want the bases closed and point to a warning from the past. In 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis, American nuclear missiles were ordered to be launched at China, Russia and North Korea by an officer who, it appears, had lost his mind. Only luck – and the vigilance of another officer – allowed his moment of madness to be countermanded. In a memorable sequence, one of the 1962 missile crew describes how the world was almost destroyed ‘by mistake’.

In 2015, Pilger reports, the US Navy and its regional allies, including Australia, rehearsed a blockade that would cut China’s lifelines of oil, trade and raw materials. Today, President Trump is waging a trade war against China, where the United States’s biggest companies, such as Apple, are based: the source of a trade deficit for which China is cast, in Trump’s world, as the ‘bad guy’. In the meantime, China has built military airstrips in the disputed Spratly Islands, in the South China Sea, and is reported to have placed its nuclear missiles on ‘high alert’.

The Coming War on China was broadcast on ITV in the UK and SBS in Australia, and seen in many other countries, including China, where a pirated version was shown to possibly its biggest audience. ‘It’s not the fairest way to distribute a film,’ said Pilger, ‘but I was delighted. The true story of China and America needs to be told, especially in Australia, where, fuelled by America, an anti-China propaganda campaign seems to be inviting a military reaction.’