Of all his films, John Pilger marked the making of Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy, about genocide in East Timor following the Indonesian dictatorship’s 1975 bloody invasion and occupation, as ‘the most challenging to my sense of self-preservation and the most inspirational’.

With small Hi-8 video cameras concealed in their bags, Pilger and director David Munro entered the country clandestinely, then posed as representatives of a travel firm. They were joined by journalist Christopher Wenner – credited as Max Stahl to protect his identity – who in 1991 had courageously filmed a massacre of up to 180 civilians in the capital Dili’s Santa Cruz cemetery. The fourth member of their team was a London doctor, who remained anonymous. ‘All of us had cameras,’ said Pilger, ‘so that, if one or more were caught, some film would get out.’

Eyewitnesses describe how whole communities were murdered resisting the Indonesian invasion and others died in concentration camps and in often unreported atrocities. A report to the Australian Parliament estimated that 200,000 had died violently or starved: a third of the population.

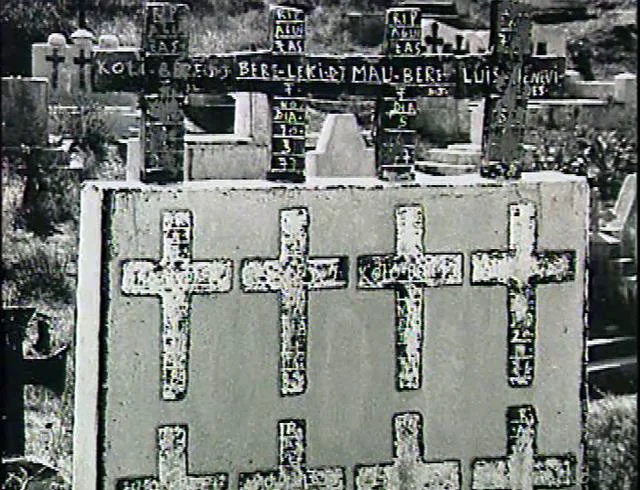

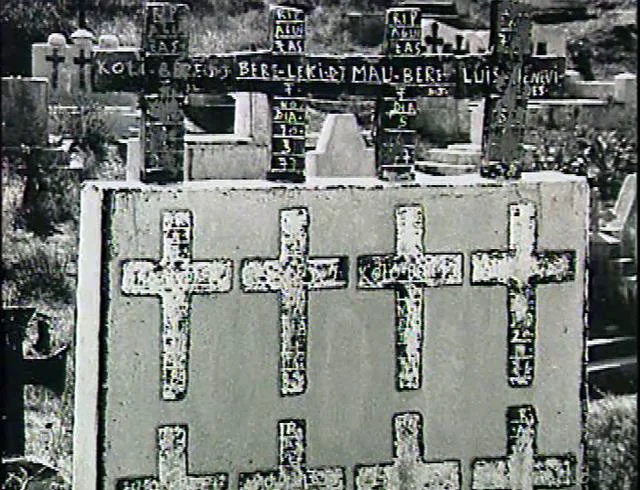

‘I had with me a hand-drawn map of where to find a mass grave,’ said Pilger. ‘I had no idea that much of the country was a mass grave, marked by legions of crosses that march all the way from Tata Mai Lau, the highest peak, 10,000 feet above sea level, down to Lake Tacitolu, where there is a crescent of hard, salt sand beneath which lie countless human remains, local people told me.’

In a memorable moment, standing on the edge of this mass grave under cover of dusk, Pilger reads a selection of diplomatic messages sent from Jakarta, Indonesia’s capital, by the British, Australian and American ambassadors: damning evidence of their governments’ collusion in an Asian holocaust.

The West regarded Indonesia in the hands of the dictator General Suharto as an investors’ paradise with a huge market in oil and other natural resources. President Richard Nixon called Indonesia ‘the greatest prize in South-East Asia’.

There is a famous sequence in Death of a Nation shot on board an Australian aircraft flying over the Timor Sea. A party is in progress. Two men in suits are toasting each other in champagne. ‘This is a uniquely historical moment,’ babbles one of them, ‘that is truly, uniquely historical.’

This is Australia’s foreign minister, Gareth Evans. The other man is Ali Alatas, Suharto’s man. It is 1989 and they are making a symbolic flight to celebrate a piratical deal they called a ‘treaty’. This allowed Australia, the Suharto dictatorship and the international oil companies to divide the spoils of East Timor’s oil and gas resources.

Thanks to Evans and Prime Minister Paul Keating – who regarded Suharto as a father figure – Australia distinguished itself as the only Western country formally to recognise Suharto’s genocidal conquest. The prize, said Evans, was ‘zillions’ of dollars.

One of the film’s whistleblowers is a former CIA officer, C Philip Liechty, who was based in Jakarta during the Indonesian takeover of East Timor in 1975. He says, ‘Suharto was given the green light [by the US] to do what he did. We supplied them with everything they needed [from] MI6 rifles [to] US military logistical support… When the atrocities began to appear in the CIA reporting, the way they dealt with these was to cover them up as long as possible.’ Pilger asks Liechty what would have happened had someone spoken out. ‘Your career would end,’ he replies.

Death of a Nation is journalism and history as topical today as it was almost a quarter of a century ago. Claud Cockburn’s maxim ‘Never believe anything until it is officially denied’ echoes through a series of extraordinary encounters in the United Nations in New York, Washington, Sydney, Lisbon. It is a story of state violence, betrayal and heroism.

The broadcasting of Death of a Nation in Britain elicited an unprecedented response, according to British Telecom, which recorded more than 4,000 calls a minute to a helpline number. Several thousand people wrote to their MPs, while members of the UN Human Rights Commission credited the documentary with influencing their subsequent decision to send a special rapporteur on extrajudicial executions to East Timor to investigate massacres such as that at the Santa Cruz cemetery.

Jose Ramos-Horta, East Timor’s foreign minister-in-exile and later its first president, said, ‘Our struggle for the recognition of our human rights was in the doldrums until Death of a Nation was shown around the world. It changed everything for us. It gave us a visual and factual point of reference – something we could show to governments and say: “Do you find this acceptable?” I have no doubt it was crucial in bringing forward our liberation and saving countless lives.’

The documentary was edited and updated in 1999 under its subsidiary title of The Timor Conspiracy following the overthrow of Suharto in Indonesia. That year, Indonesia surrendered control of East Timor, which finally achieved its struggle for independence in 2002.