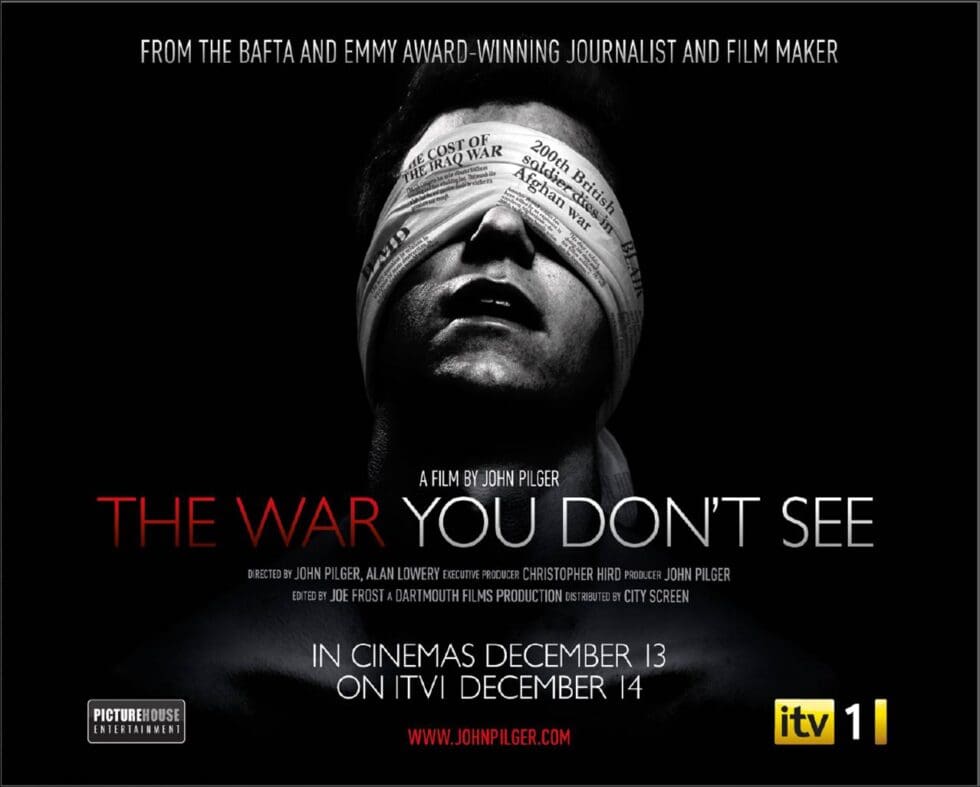

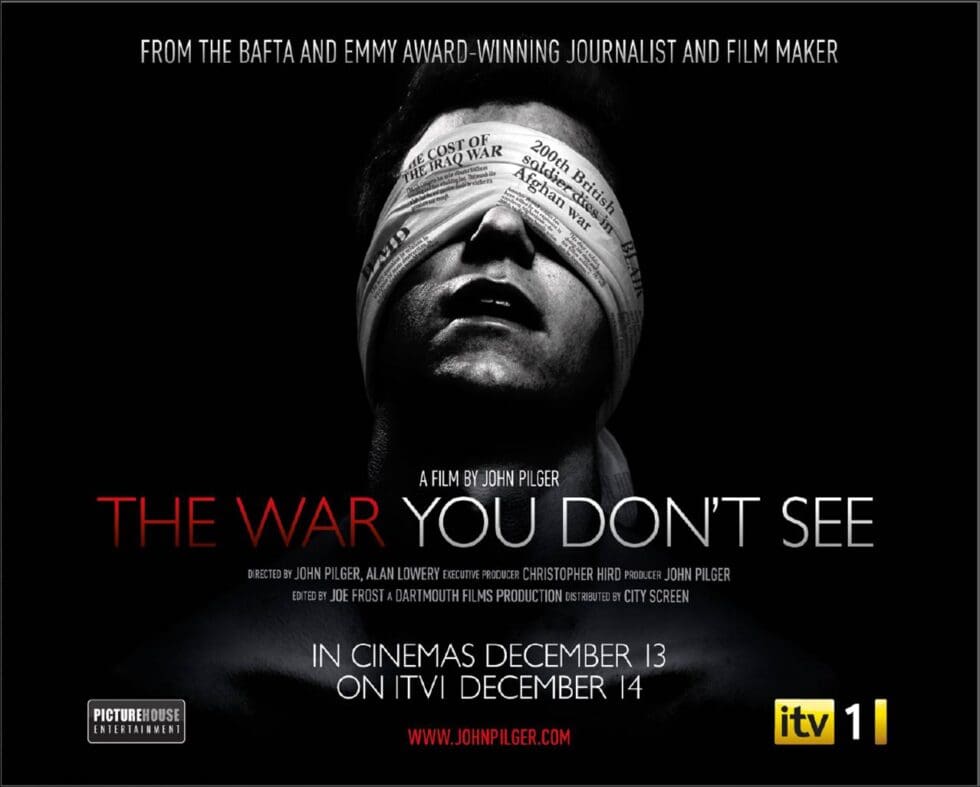

Powerful investigation into the media’s role in war, tracing the history of ’embedded’ and independent reporting.

In The War You Don’t See, John Pilger returns to the subject of war reporting and its critical role in the making of wars. This ‘drum beat’ was the theme of Pilger’s 1983 documentary Frontline: The Search for Truth in Wartime, a history of war journalism from the Crimea in the 19th century (‘the last British war without censorship’) to Margaret Thatcher’s Falklands War in 1982.

The War You Don’t See analyses propaganda as a weapon in Iraq and Afghanistan. The title refers to censorship by omission – ‘the most virulent form of censorship,’ said Pilger – and the collusion of journalists in nominally free societies such as Britain and the United States.

The film begins with shocking footage from Iraq in 2007. An American Apache gunship opens fire on a Baghdad street, killing in cold blood two Reuter journalists, along with Iraqi civilians. There is no provocation – the victims are unarmed. One of the Apache crew comments ‘Nice’ as he murders people at a safe distance. Titled ‘Collateral Murder’, the video was leaked to WikiLeaks by soldier Bradley (later Chelsea) Manning.

‘Selling’ the 2003 invasion of Iraq is the centrepiece of Pilger’s film. The news media is exposed as a source of illusions, such as a non-existent link between Saddam Hussein and the attacks of 9/11. A CIA witness says the primary aim of intelligence supplied by the Pentagon is to manipulate public opinion.

In a series of remarkable interviews, prominent journalists in Britain and the United agree that, had they and their colleagues challenged rather than amplified and echoed the deceptions of their governments, the invasion of Iraq might not have happened.

Former CBS newscaster Dan Rather tells Pilger that ‘tough, digging, aggressive questions’ might have prevented the war, while Rageh Omaar, the BBC’s man in Iraq, says, ‘We failed to press the most uncomfortable buttons hard enough,’ and reporter David Rose – who campaigned in The Observer for the invasion – refers to ‘the pack of lies fed to me by a fairly sophisticated disinformation campaign’ and agrees that journalists are guilty of war crimes.

Perspectives such as these, coming from a notoriously defensive industry, are rare – as is the appearance of the editor-in-chief of ITV News and the BBC’s head of newsgathering, who defend an institutional bias, not altogether convincingly.

Previously unscreened footage shows a 2004 attack on the Iraqi city of Fallujah by American and British forces that left thousands dead. An independent American journalist’s report and photographs of mass graves never appeared in mainstream media. In occupied Palestine, reports Pilger, the intimidation and killing of non-Western journalists by the Israelis are seldom reported.

The War You Don’t See marks the rise of WikiLeaks, whose founder and editor-in-chief, Julian Assange, tells Pilger that his organisation gives ‘conscientious objectors’ within ‘power systems’ a means of informing the public directly, a landmark in journalism.

‘The lives of countless men, women and children depend on the truth,’ concludes Pilger, ‘or their blood is on those of us who are meant to keep the record straight.’