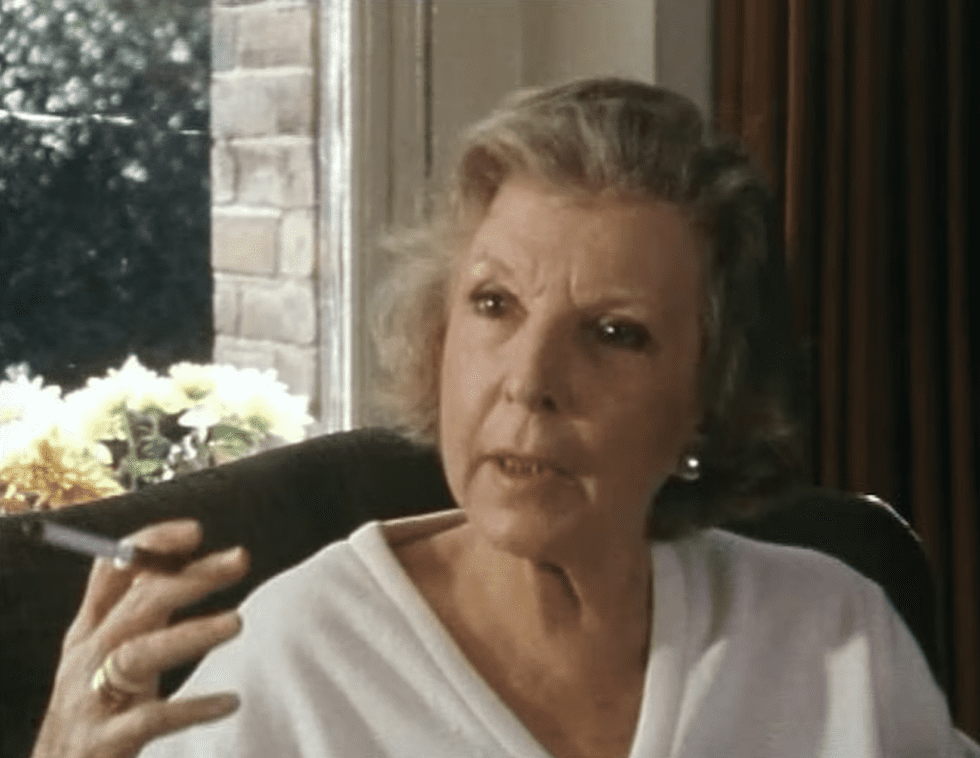

John Pilger talks to Martha Gellhorn

John Pilger has always considered himself an ‘outsider’ – that is, a journalist who believes ‘received wisdoms’ should be questioned. In 1983, Britain’s newly launched Channel 4 broadcast nine face-to-face interviews by Pilger entitled The Outsiders.

In deciding on his subjects, Pilger chose ‘those who have challenged orthodox ideas that lead us in the same direction’ – and added a rider: he or she must have demonstrated the courage of his or her convictions.

No one fitted this description more than Martha Gellhorn, one of the great witnesses of the 20th century. She was also the inspiration for Pilger’s early reporting on the Vietnam War. In a famous series of dispatches from Saigon in 1967, she described the American invasion as ‘a new kind of war… a war on civilians’. In The Outsiders, Gellhorn tells Pilger she regarded the entire war as ‘an act of criminal stupidity’.

The daughter of a suffragette and a distinguished medical specialist, Gellhorn was, says Pilger in his introduction, the world’s first accredited female war correspondent, who invariably wrote from the point of view of the victims of war. She called this ‘the view from the ground’.

She reported the Spanish Civil War from the defeated Republican side, whose cause she embraced, and later saw front-line action in China, Finland, the Second World War, Vietnam and El Salvador.

Her first successful book, The Trouble I’ve Seen, was based on her experience as a field investigator for President Franklin Roosevelt’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration during the Great Depression of the 1930s. She tells Pilger that she was sacked after inciting a group of unemployed men to break the windows of a relief office in Idaho to ‘get the attention of authority’.

The Spanish Civil War left a deep impression on Gellhorn. Asked by Pilger for her lasting memory, she replies, ‘The enormous bravery of the people, absolutely unbelievable bravery under appalling conditions.’ It was in Spain that she met Ernest Hemingway and became his third wife.

At the end of the Second World War, Gellhorn entered Dachau on the day of liberation. Reporting this, the first German concentration camp, had been her personal war aim. ‘It was a total and absolute horror, and all I did was report it as it was,’ she says. ‘I got out of Dachau in a state bordering on uncontrolled hysteria.’

She tells Pilger she still has hope. ‘I think the world is just as awful as it can be at any given moment,’ she says. ‘There will always be a certain number of people fighting like hell from keeping it being unbearably worse.’

In her 70s, she reported the US invasion of Panama and was so appalled by the loss of civilian life that she flew to Washington and confronted a general at a Pentagon press briefing. In her 80s, she wrote movingly about Brazil’s street children.

She and Pilger became close friends and when she died in 1998, aged 89, he and other ‘cronies’ initiated the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism, which is today a prestigious award given to journalists who ‘reach behind the facade of propaganda and expose, in Martha Gellhorn’s words, “official drivel”’